- Christina Sumners

- Medicine, Research, Show on VR homepage

Exploring new approaches to PTSD treatment

Texas A&M researchers looking at new ways to treat PTSD, reduce symptoms

When veterans were returning from World War I, they coined a new term, “shell shock,” to describe the fatigue, confusion, nightmares and lack of functioning they experienced. Today, this condition is called post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and it is now recognized as a medical issue requiring treatment.

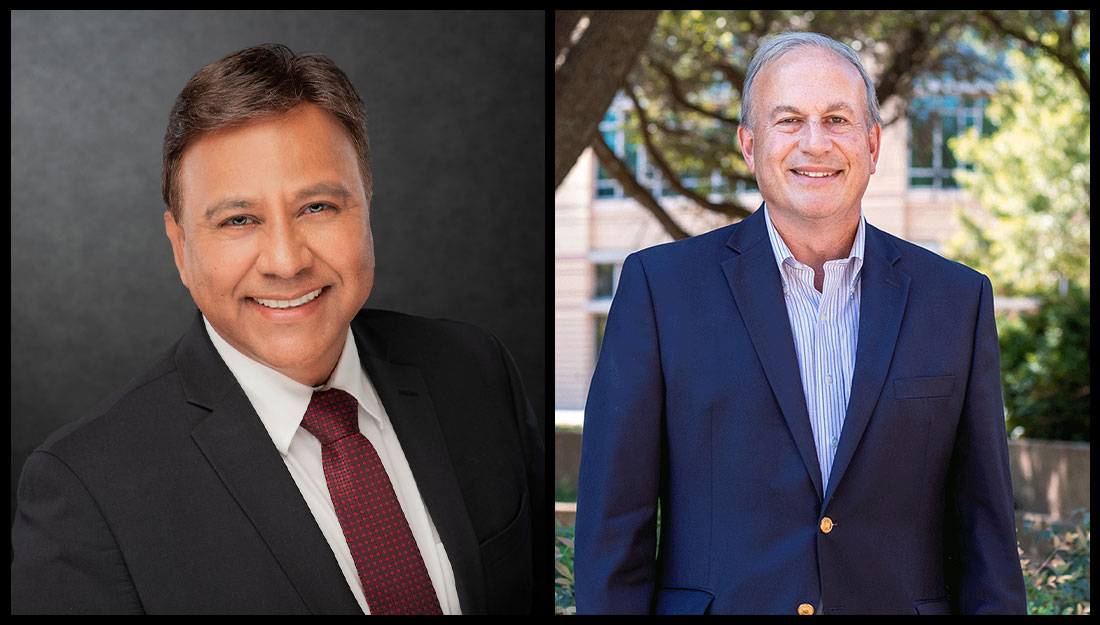

About 23 percent of Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans meet criteria for PTSD, according to Eric Meyer, PhD, associate professor at the Texas A&M College of Medicine and a clinical psychologist at the United States Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) VISN 17 Center of Excellence for Research on Returning War Veterans, located at the Waco campus of the Central Texas Veterans Health Care System. Although researchers and health care providers are starting to better understand the underlying brain functions, there is no perfect treatment.

“It’s a good news, bad news story,” Meyer said. “We have several treatments that are effective, to a large extent, for many veterans. However, many veterans don’t benefit as much as we would like. That spurs people like me to explore what other treatment options might be tried and how we could augment or make modifications to the existing treatments to make them more effective.”

The current first-line cognitive-behavioral treatments, which are backed by numerous studies supporting their effectiveness, require veterans to engage with the memories of their traumatic experiences. “Many simply won’t do it,” Meyer said, “and many of those who do begin therapy drop out because successful treatment can involve a short-term period of increased distress before they start to get better.”

The other problem is that PTSD commonly occurs alongside other issues, including other forms of anxiety, depression, misuse of alcohol and often—especially in war veterans—chronic pain. “It’s a complex mental health picture,” Meyer said. “Psychological treatments are superior to medication for treating PTSD, but even after treatment, many veterans are still experiencing a high level of symptoms.”

Therefore, Meyer and others are looking at a new approach that focuses on integrating behavior therapy and mindfulness. Mindfulness training involves learning to connect one’s focus to the present moment. “People who have experienced trauma spend a lot of time dwelling on past events, and PTSD and anxiety are also strongly associated with dread or worry about the future,” Meyer said. “So, what gets lost? The present, when we’re actually alive, and that’s where mindfulness training can help.”

Mindfulness training involves structured exercises aimed at focusing on some aspect of one’s experience in the moment in an open, non-judgmental way. That can be done through noticing the breath, noticing thoughts or feelings, or some other aspect of present-moment experience. There are many free mindfulness exercises online and available on apps for anyone interested in practicing mindfulness. “Practicing acceptance of unwanted thoughts and feelings involves using mindfulness skills when having these experiences and engaging in behavioral exercises so that the person practices mindfulness and acceptance in real-world situations,” Meyer said. “All of this is done in the service of helping people engage in activities that are meaningful to them.”

Meyer is directing a VA-funded longitudinal research program studying nearly 700 Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans called Project SERVE. This study, which is in its third funded phase that will continue through June of 2018, is examining mental health outcomes as well as problems with readjustment such as employment problems and difficulties with relationships. The study is focusing on modifiable psychological factors, including mindfulness. Among the study’s key findings is that veterans’ level of mindfulness predicts their level of functioning and disability after accounting for their level of PTSD symptoms. This study is also collecting blood samples for genetic analyses that will occur in the near future.

Meyer is also interested in the related concept of acceptance. His research has demonstrated that one example of the clinical importance of acceptance is that veterans who take a more acceptance-based approach to living with chronic pain experience less disability related to their pain, even after controlling for pain severity and other important factors like depression and traumatic brain injury. He thinks an acceptance-based approach might also be effective for veterans struggling with both PTSD and alcohol use problems. “Mindfulness, self-compassion and acceptance predict how well veterans are readjusting, no matter how severe their initial symptoms were,” Meyer said. “As far as I know, we’re the first ones to test this approach to treating veterans with both PTSD and alcohol problems.”

Meyer is also collaborating with colleagues in San Antonio and Boston on pilot testing with student veterans of what is called written exposure therapy, in which people write about their experiences in a brief, highly structured way.

“It’s a gentler—and possibly just as effective—approach to doing trauma-focused work,” he said. “We thought student veterans would be a natural fit because they’re used to writing, and it seems to have lower dropout rates than standard exposure therapy.”

“We may not be able to make the unwanted thoughts, feelings and memories go away, but we can help people relate to them in a more helpful way,” Meyer added. “There are multiple factors that interact in complex ways to impact veterans’ ability to readjust after serving in a war. We need to improve our treatment approaches as new data emerge that point the way toward additional factors that we can target to help veterans improve their lives.”

Media contact: media@tamu.edu