- Mary Leigh Meyer

- Medicine, Show on VR homepage, Trending

Fast facts: Measles comeback

With the recent measles outbreak, we discuss what you need to know to protect yourself and your family

Measles, mumps and rubella vaccination sign pointing to a clinic

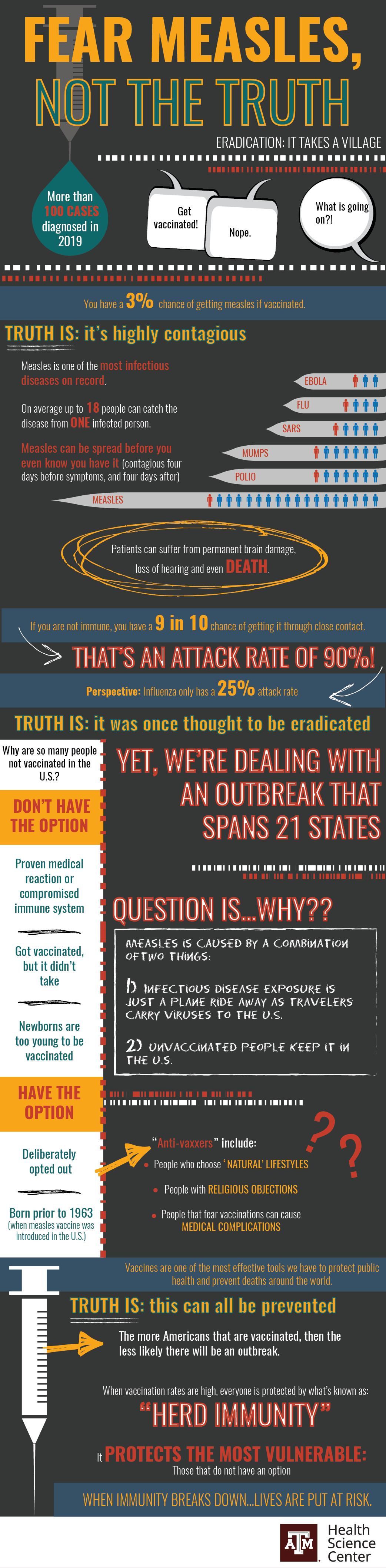

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported 79 active, individual cases of measles across 10 states during January 2019. The average American no longer knows much about the virus, since its United States eradication over a decade ago. However, with measles now infecting people across the United States, it’s important to know the basics.

We sat down with infectious disease expert, Cristie Columbus, MD, associate dean for the Texas A&M College of Medicine, to find out more about how this highly contagious respiratory disease spreads and how it can be prevented.

Q: What are the symptoms of measles?

A: Patients suffering from measles usually present with a high fever, cough, runny nose and red, watery eyes that typically appear about seven to 21 days after infection. Several days after symptoms begin, a red rash breaks out on the face and spreads to the rest of the body.

Q: Is measles serious?

A: Measles is one of the most contagious infectious diseases that affect humans. Severe complications can occur, including pneumonia, encephalitis (swelling of the brain) and even death. Those with compromised immune systems, children under 5 and adults over 20 are more likely to develop severe complications. According to the CDC, approximately one in 1,000 to 2,000 patients with measles will have swelling of the brain and approximately six percent of all measles cases will get pneumonia.

Q: How do you prevent measles?

A: Immunization is the most effective method of preventing measles and its complications. Measles is extraordinarily contagious. Doctor’s offices and emergency rooms prefer you isolate yourself and call ahead if you believe that you might have measles. This will prevent others from contracting the disease from you in a public venue.

Q: How is measles spread?

A: Like many airborne infectious diseases, measles is spread primarily through coughing and sneezing, but the pathogen can live on surfaces for up to two hours. Studies documented disease transmission in closed areas (such as physician exam rooms) for up to two hours after an infected individual has been present. It is important to note that individuals are contagious up to four days before and up to four days after the rash appears. Unfortunately, it is also possible to catch measles from someone before they have developed the characteristic rash.

Measles is highly contagious to persons without the vaccination. Without immunity, you have approximately a 90 percent chance of catching measles if you are in the same areas as an infected individual. However, measles does not require close contact with an infected person for transmission.

Q: How effective is the measles vaccine?

A: Measles can be prevented with the measles, mumps, and rubella, or MMR, vaccine. In the United States, widespread use of the vaccine has led to a greater than 99 percent reduction in measles cases compared with the pre-vaccine era. In short, the vaccine is highly effective. Before the measles vaccination program started in 1963, an estimated three to four million people got the disease each year in the United States. While overall number of measles cases reported in the United States has decreased dramatically, it is on the rise again.

Q: Who should get the vaccine?

A: CDC recommends all children get two doses of MMR vaccine. The first dose at 12 to 15 months and the second dose at 4 to 6 years. The CDC urges adults without evidence of immunity from vaccine records or laboratory tests to get vaccinated.

Q: I thought measles was eradicated in the United States. Why is it back?

A: Measles transmission was eliminated in 2000 when the United States went 12 months without disease transmission. Unfortunately, vaccination rates have declined in the United States, which gives the disease more room to spread.

Fortunately, the more Americans that are vaccinated, then the less likely the United States will sustain an outbreak. In other words, the virus can infect fewer unvaccinated persons, when vaccinations are high. As a consequence, sustained person-to-person measles transmission is difficult in this situation. We call this public health phenomenon “herd immunity.”

“Herd immunity” confers an indirect benefit to persons in the population who cannot be vaccinated, like children under the age of 12 months, immunocompromised individuals, persons with severe allergic reactions to the vaccine and pregnant persons. In general, we need a 95 percent rate of immunization to stop it from spreading within a community.

Vaccinations protect not only the immunized individual, but they also indirectly protect others in the community. Vaccines remain one of the most effective tools we have to protect public health and prevent deaths around the world.

Media contact: media@tamu.edu