- Christina Sumners

- Public Health, Show on VR homepage, Trending

What you should know about Zika

As mosquitoes venture out of their geographical habitat, so do the viruses they carry

As the Zika virus captures headlines as a global health emergency, with its link to birth defects and a rare autoimmune disorder, it’s an opportune time to review the facts. Texas A&M experts explain the virus, track its spread and put fears in context.

Q: What is the Zika virus?

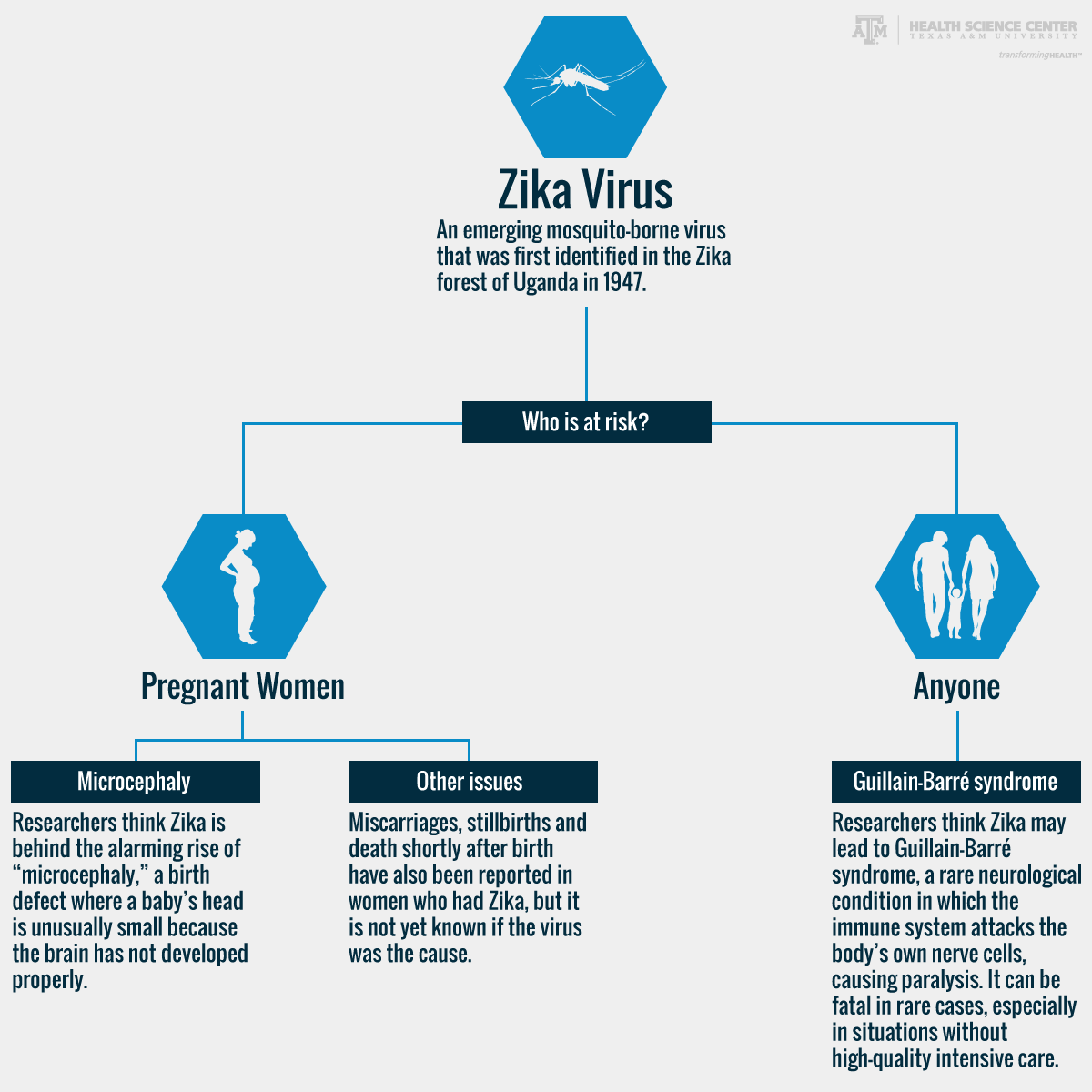

A: A member of the Flavivirus family, the Zika virus is an emerging mosquito-borne virus that was first identified in the Zika forest of Uganda in 1947. Until very recently, it was confined to Africa with occasional small outbreaks in Asia. It slowly spread east, with cases on Easter Island off the coast of South America confirmed in 2014 and the first cases in Brazil in spring of 2015, and it has spread further throughout South and Central America since then. Although usually a mild illness, the virus can be dangerous to pregnant women and their unborn children.

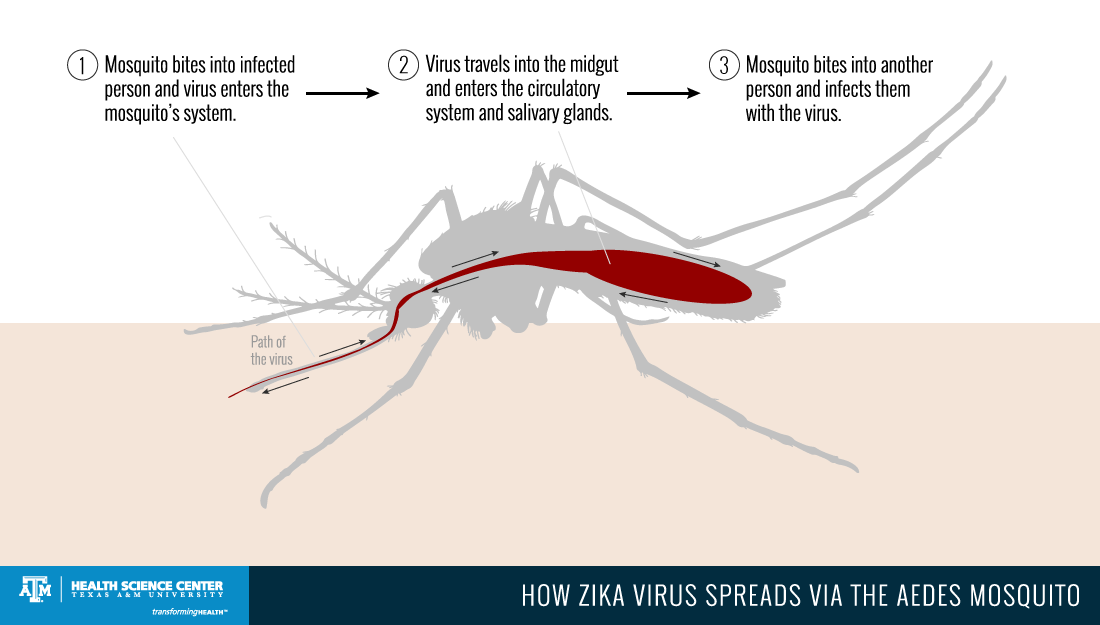

Q: How do you get Zika?

A: Like a number of other diseases such as dengue and chikungunya, which are also spread by mosquitoes, the Zika virus is spread through the bite of the Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus species of mosquitoes. Mosquitoes become infected when they bite a human who has the virus, and are then capable of spreading the virus to other susceptible humans. These mosquito vectors are abundant in many urban environments of Texas and elsewhere and are active during the day and night, increasing the period that humans are at risk of exposure. Between 20 and 25 percent of those infected will develop symptoms. It’s been shown that the virus can be spread through sexual transmission from human to human, but that mode of transmission remains rare.

Q: What are the symptoms?

A: Common symptoms of Zika include fever, skin rash, red eyes and joint pain. Some patients report muscle pain, general malaise, headache and vomiting. Symptoms typically last between two and seven days. Complications are rare, but some cases require hospitalization for supportive care.

Q: Who is at risk?

A: Everyone who hasn’t had the virus is potentially at risk. For pregnant women, contracting the virus represents a risk to her unborn baby. Researchers think Zika is behind the alarming rise in miscarriages and microcephaly, a birth defect in which the infant has an unusually small head and abnormal brain development. For everyone else, the biggest potential complication is Guillain-Barré syndrome, in which the immune system attacks the body’s own nerve cells, causing problems with muscle coordination and breathing. It can be fatal in rare cases, especially in situations without high-quality intensive care.

Q: Is there a treatment?

A: No, other than making the patient more comfortable with symptomatic treatment, there is no specific cure or treatment for Zika. There is also no cure for Guillain-Barré syndrome, although supportive measures in the intensive care unit can typically keep patients alive long enough to recover.

Q: How can the virus be prevented? How can I protect myself?

A: There is no vaccine for the virus yet, so all preventive measures should be focused on preventing mosquito bites. This means eliminating standing water and other mosquito breeding sites, as well as using mosquito screens in windows and using appropriate insect repellents when outdoors. People who might be infected should use condoms or abstain from sex to avoid infecting their partners.

Q: How is Zika diagnosed? Are there tests available?

A: The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a test that is available to laboratories certified by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The test looks for the antibodies that Zika causes the body to make, but it’s not 100 percent accurate. A positive test could mean the person was infected with a similar virus, and a negative test doesn’t necessarily mean the person didn’t have Zika—just that the antibody levels were too low for the test to detect.

Q: What do pregnant women need to know about the virus?

A: The Ministry of Health of Brazil discovered an association between being infected with Zika virus and an increase in cases of microcephaly in newborns in that county, with the risk greatest when the mother was infected during her first trimester. Microcephaly is a medical condition that results in a small head because the brain has stopped growing or is not developing properly. Because of the association between Zika virus infection and microcephaly, pregnant women should be especially careful to avoid mosquito bites, particularly during the first trimester. The CDC has advised pregnant women to avoid travel to endemic areas if possible. Because many women do not know they’re pregnant until near the end of the first trimester, women who could be pregnant should also consider taking precautions.

Q: Where is Zika?

A: A number of countries in the Americas from Mexico to Brazil have active Zika transmission. In addition, Cape Verde and three Pacific Islands (American Samoa, Samoa and Tonga) have reported transmission of the virus. Recently, cases involving local transmission have been reported in two areas of Miami, Florida and in South Texas. We have also seen the Zika virus in travelers returning home from places where Zika is spreading and their sexual partners.

Q: Will we see Zika in more of the United States?

A: We’ve seen several cases of Zika that were likely acquired in Florida and Texas, and sporadic cases may continue to occur in areas where the Aedes mosquito is present. However, health officials are not anticipating widespread outbreaks in the continental United States. Crowded tropical areas without air conditioning or window screens are prime opportunities for spread of the virus, while screened-in spaces and air conditioning common in the United States helps to block virus transmission by reducing contact between mosquitoes and humans.

Q: Now that Zika is being transmitted in the continental United States, what should I do?

Physicians are not necessarily suggesting that their pregnant patients leave Florida or Texas at this point, but everyone should take basic precautions like using insect repellant and getting rid of standing water around the home. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is now recommending that pregnant women avoid visiting the areas of Miami where Zika is spreading.

Q: What if I’m planning to travel to a place with an established Zika outbreak?

A: Pregnant women are being advised to avoid areas with active Zika transmission if possible. The CDC recommends usual anti-mosquito measures for everyone, pregnant or not. Men returning from active Zika transmission areas should use condoms to protect their partners from possible infection, especially if his partner is or could be pregnant. Officials are also urging travelers to avoid mosquito bites both while in a Zika-affected area and for at least a week after a returning (in order to avoid spreading the virus, should they be infected and not know it.)

Q: What should I do if I think I might be infected with Zika virus?

A: To prevent others from getting sick, it is especially important to keep any mosquitoes from biting you and transmitting the virus to other people. Get plenty of rest and drink fluids to prevent dehydration. Pregnant women potentially exposed to Zika virus (through either travel to or contact with a partner who has travelled to a Zika-endemic region) should notify their obstetrician so that maternal and fetal screening tests can be initiated.

For additional information, visit the CDC website.

Media contact: media@tamu.edu