New interdisciplinary research lays groundwork for predicting if bone cancer will spread

Bone pain. Joint pain. Bone swelling. These are symptoms that about 1,000 people in the United States begin to feel each year shortly before being diagnosed with osteosarcoma, a type of cancer that starts in the bones. Although any age can develop osteosarcoma, approximately half of diagnosed cases are in children and adolescents.

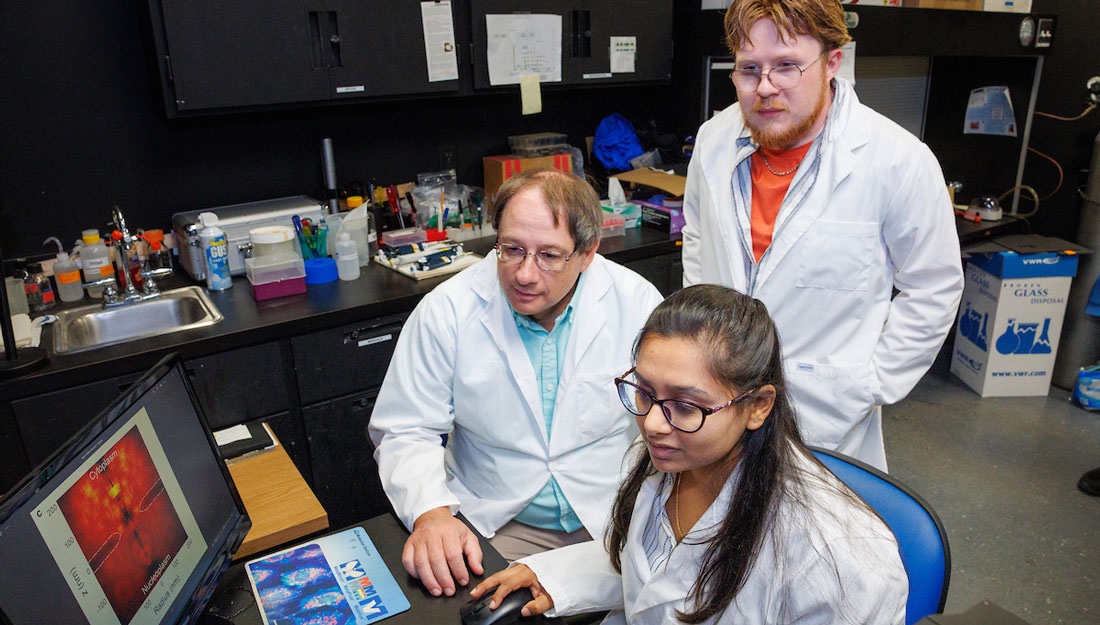

New interdisciplinary research is highlighting this rare bone cancer, specifically relating to the probability of metastasizing, or spreading, to another part of the body. Irtisha Singh, PhD, assistant professor at the Texas A&M University College of Medicine, and Jason T. Yustein, MD, PhD, professor at the Winship Cancer Institute and the Aflac Cancer and Blood Disorders Center at Emory University, joined forces and their combined expertise to examine the cancer at the molecular level.

Singh explained that every person has a unique set of genes, each contributing to varying levels of gene expression. This variation allows cells in different parts of the body to perform distinct functions.

“The cells in your blood versus the cells in your skin have very different functions, which means that although they have the same DNA, they are expressing a very different set of genes,” Singh said.

Through this research, Singh and Yustein aim to uncover why some cells become cancerous and metastasize, while others may not, even if they turn cancerous. The team believes differences in epigenetic states influence gene expression, and thus play a key role in how cancer behaves. Dysregulation of cells, driven by these epigenetic changes, appears to underlie this behavior.

Early evidence suggests that certain epigenetic states and gene expression profiles could indicate whether a tumor is likely to metastasize, even at early stages before traditional methods can detect such risks. This study provides a promising pathway to predict metastatic potential earlier, which could enable targeted interventions for patients.

Yustein saw osteosarcoma patients in the clinic. A subgroup of osteosarcoma patients experienced detectable metastasis of their cancer at the time of their diagnosis. This led the team to believe that there is something fundamentally different with the epigenetic landscape of the tumors that showed evidence of metastasis from the tumors that did not metastasize. So, Yustein began examining the samples at the most basic level.

“He took these biopsies and created patient-derived xenografts, and then we went ahead and did epigenetic profiling and gene expression profiling of these samples,” Singh said. “Then we compared to see if we see some fundamental changes in the two groups of patients.”

The team found that the epigenetic state of cells plays a strong role in determining gene expression, and therefore probability of tumor metastasis. Singh explained that whether a gene is “turned on” depends on how the DNA is packed. When DNA is tightly wrapped around proteins called histones, the genes stay off. But if the histone proteins have certain chemical modifications, or epigenetic states, it becomes looser and easier to read.

These changes make it possible for the cell to turn those genes on and make RNA from them, which are then converted into proteins. This allows the genes that facilitate metastasis to be expressed and cause some tumor cells to metastasize. The changes in these cells make them fundamentally different from other tumors that do not metastasize, which could make it possible for practitioners to someday predict metastasis before it happens.

“The key highlight for me for this research was that normally the way we think about cancer, especially the ones that metastasize, is that you have the same kind of cancer across patients and then somehow certain cells gain these special abilities to move away from the primary site and that’s when metastasis happens,” Singh said. “But from this research, what really came out was that at the fundamental level, the primary osteosarcoma tumors are very different, so maybe even ahead of time you can tell that these patients will undergo metastasis versus not.”

Unlike other cancers, osteosarcoma survival rates have not significantly improved in the past 20-30 years, especially for those patients with metastatic disease, which is why Singh believes this research is so vital. Future studies will focus on how to translate these findings toward identifying better treatments for patients with metastasis or those at risk for developing metastatic osteosarcoma.

The team is working on expanding this research by examining other types of sarcomas, like rhabdomyosarcoma—a cancer closely related to osteosarcoma.

Media contact: media@tamu.edu