- Christina Sumners

- Medicine, Nursing, Show on VR homepage

Texas’ alarming maternal mortality rates

How the state and the nation are failing to prevent pregnant women and new mothers from dying—and what can be done about it

There have been a number of stories in the media recently about women dying or nearly dying during pregnancy or shortly postpartum. Once thought of as a largely historical issue, or one that only affected women in the developing world without access to modern medicine, people around the country seem to be increasingly recognizing the problem. And it is indeed a problem: The United States has the worst maternal mortality rate of any developed country, with an estimated 26.4 maternal deaths for every 100,000 live births in 2015. Perhaps just as alarming, this number has been rising since 1990 while the rate of most other countries in the world is dropping. In fact, the United States was one of eight countries where maternal death rates worsened between 2003 and 2013.

Texas has a high number of pregnancy-related deaths when compared to other states. “Our death rate in Texas has gone up,” said Shelley White-Corey, MSN, registered nurse and women’s health nurse practitioner and a clinical assistant professor at the Texas A&M College of Nursing. “Some states, like California for example, are doing a good job bringing their numbers down, but we haven’t been able to do the same for reasons that aren’t quite clear. However, there are certain factors that we know put women at higher risk of complications.”

Some of these risk factors are increased maternal age. In the United States, more first-time pregnancies are occurring in older women, with more complex medical histories, than in previous years. “Additionally, half of all pregnancies in the United States are unplanned, so many women with chronic medical issues like hypertension or diabetes do not seek medical stabilization before pregnancy occurs,” said Hector O. Chapa, MD, FACOG, clinical assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the Texas A&M College of Medicine.

It’s also perhaps maternal mortality’s relative rareness—at least compared to deaths from conditions like cancer or heart disease—that makes it especially difficult to combat when it does occur.

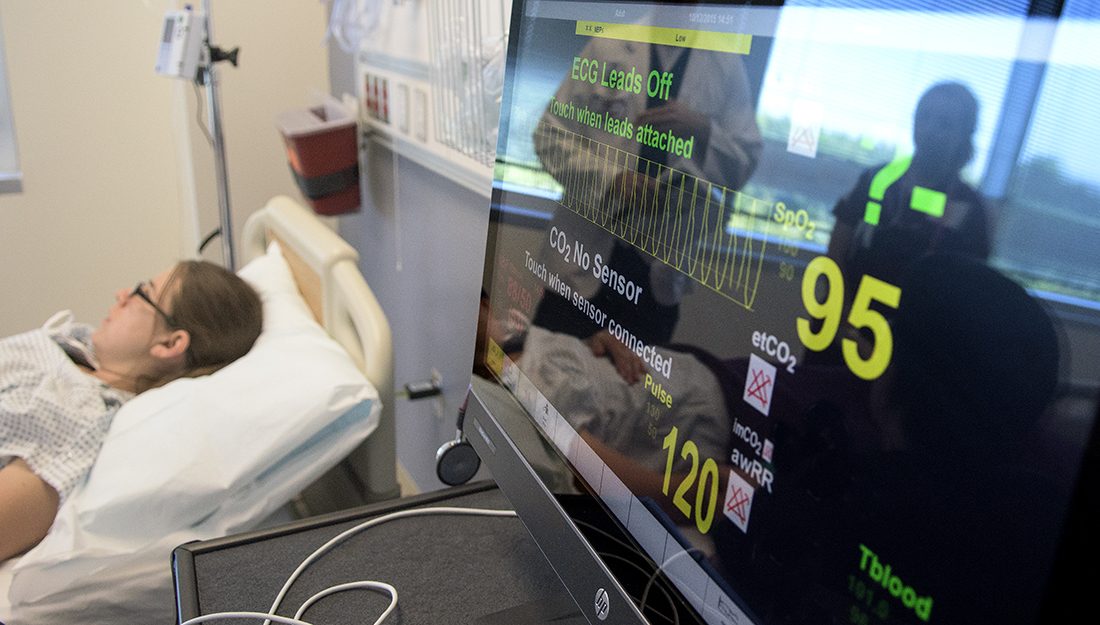

“Childbirth complications don’t happen very often, but when they do, it can be serious,” White-Corey said. That’s why the Texas A&M Colleges of Nursing and Medicine conduct simulations to train future physicians and nurses how to respond to these sorts of pregnancy and birth complications before they ever enter a clinic or hospital.

“One of the things we stress to our students in our simulation is how important it is to have a well-functioning team because we don’t have time for communication breakdowns,” White Corey added. “Someone needs to take charge of the situation or you won’t have a good outcome for the mother and the baby.”

On a larger scale, Texas is trying to address the issue by extending the work of a state Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Task Force through 2023 and by having the task force study what other states are doing to curb their own rates. The legislature also added a labor and delivery nurse and a critical care physician to the task force. “I think these are positive steps that will hopefully help us lower the rate of new mothers dying in Texas,” White-Corey said.

Oddly, however, this issue of increasing maternal mortality is in paradox to perinatal mortality. Infant mortality has fallen to its lowest rate in over 30 years. Organizations like the March of Dimes, together with advocacy groups for women’s care, have brought attention to things like elective cesarean sections and their potential risks, early elective inductions and other pregnancy conditions that have now been addressed to improve neonatal outcomes.

Of course, sometimes inducing labor is necessary for the health of the mother or the baby. Thanks to Kim Kardashian West having the condition, many more people now have heard of placenta accreta, a potentially dangerous condition in which the placenta attaches itself too deeply to the uterine wall. This can lead to the mother losing more blood than her body can handle very quickly. That’s why ACOG recommends delivery at 34 weeks of gestation in an operating room ready to handle potential complications.

Unfortunately, although the condition can be seen on an ultrasound, if a woman hasn’t been receiving good prenatal care, she might not know she has placenta accreta until it is too late.

Another common reason why a physician might recommend induction of labor is preeclampsia, in which a woman develops dangerously high blood pressure that can lead to seizures or strokes. Although researchers are working on ways to reverse the condition early in a pregnancy, in the meantime, it’s important for women to know how to recognize the symptoms. “If you are pregnant and start experiencing severe headaches or right upper quadrant pain or you start seeing spots, call your provider right away,” White-Corey said.

Although these conditions specific to pregnancy, along with unforeseeable catastrophic medical events and medical errors, have featured prominently in many of the news reports of mothers dying during pregnancy or soon after, they do not explain the current maternal mortality trends, according to Chapa. “Although preventable medical errors are a known cause of patient harm nationally, and worldwide, medical errors are not the main factor at play here,” he said. “Obstetrics possesses unique maternal physiological changes that may result in devastating and catastrophic maternal events—despite advances in medical practice.”

One of the best ways to reduce the risks is to provide better access to prenatal care. “Getting care early in the pregnancy is so important because it helps catch conditions early,” White-Corey said.

Limited access to early prenatal care in lower socioeconomic groups is especially concerning, according to the Society for Maternal Fetal Medicine, because there are discrepancies in maternal mortality rates based on race and ethnicity that could be explained by differing levels of access to prenatal care early in pregnancy. “Maternal mortality in the United States, for example, disproportionately affects black women,” Chapa said. “And mothers in the lower socioeconomic groups are the ones who suffer the consequences the most.”

Unfortunately, even if they’ve had the best prenatal care, women aren’t out of the woods once the baby’s born. “Most people don’t realize that maternal suicide is one of the leading causes of death for new mothers,” White Corey said. “Many postpartum women have mood or anxiety disorders, but it’s under-discussed, underdiagnosed and undertreated.”

If women experience postpartum blues that don’t go away after a few days or if they find themselves crying for no external reason or having thoughts of hurting themselves or their babies, they need to ask for help. “Anyone with these symptoms should call her provider right away,” White-Corey said. “Many women are focused entirely on their new baby during this time, but they need to take care of themselves too, because proper treatment—whether that is therapy, medication or both—could help save lives.”

Clearly, the solution to maternal mortality will be multi-pronged, just like its causes are.

“While advances in medicine progress, the United States maternal mortality still rises,” Chapa said. “Better access to early prenatal care, maternal education, resources for low income areas and a state-specific focus on making maternal health a priority are all vital aspect to help reverse this distressing trend…one state at a time.”

Media contact: media@tamu.edu